Pittsburgh is defined by its rivers. They shape both the physical landscape and the intangible character of the city. And on any given day, provided the weather cooperates, Pittsburgh residents can be found running, biking, walking and enjoying the calming force of flowing waterways.

Those living or working Downtown are often drawn to the northern side of the city, where the Allegheny River mirrors the meandering park bearing its name. This coming November will mark the twenty-year anniversary of the Allegheny Riverfront Park opening its lower level. What may be surprising to some is that the park is a project of the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust.

What business does a cultural organization have building a public park? As it turns out, quite a bit. Allegheny Riverfront exists as more than just a park; it’s an integral piece of the Trust’s collection of public art. Even more, it serves as a gateway to the river, a connection between the revitalized Cultural District and Pittsburgh’s roots.

For many decades, though, the major waterways so vital to the Steel City weren’t readily accessible to its residents — especially not to those who lived and worked Downtown. The Golden Triangle was long surrounded by industry, bounded on all sides by rail yards, warehouses and highways.

The situation started to turn around in 1974, when construction finished on Point State Park. The city had a taste of the water, but only just. The north and south edges of Downtown were still cut off from their respective rivers by parking lots and highways. The Allegheny side had three layers of separation: Fort Duquesne Blvd., the 10th St. Bypass and a flood-prone strip of parking.

Reclaiming some of that space for use as a public park wasn’t a new idea. In fact, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. proposed a system of riverside parks for the city way back in 1911. It wasn’t until the 1990’s, however, that the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust revived the idea as part of its master plan to redevelop Downtown’s red light district into the arts-centric Cultural District. The Trust ended up commissioning a unique collaboration between landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh and artists Ann Hamilton and Michael Mercil. With that began a decade-long process of research, design and construction.

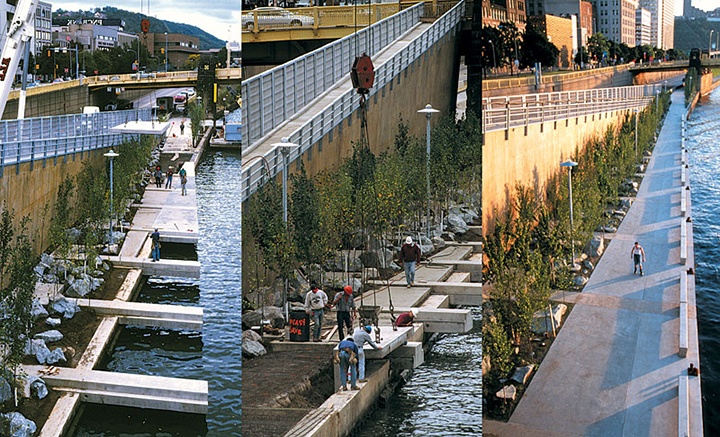

The task of transforming the space into a functional and aesthetically-pleasing park was rife with challenges. On a large scale, the team had to find a way to make a cohesive park out of a space unavoidably split by roads. With those roads also came the sights and sounds of traffic, neither of which are synonymous with the typical park experience. Ultimately the decision was made to welcome the buzz of the city, not to try and block it out.

“We all agreed the park should embrace both its natural and urban conditions,” Mercil wrote, “We placed the lower park not just beside the river, but also in and over the water’s edge.”

While it can be hard to spot when walking the riverside trail, the pathway does indeed jut out beyond the shoreline at points, cantilevered over the Allegheny with the help of heavy concrete counterweights. Pedestrians can access the path by way of two 350-foot-long ramps, each fully ADA compliant, that descend from both sides of the Andy Warhol Bridge. Steel-framed chain link walls provide foothold for vines, separating the ramps from the noise of the Tenth St. Bypass.

Artists Hamilton and Mercil sprinkled their touches throughout the span of the park. A thick, cast bronze railing, designed to imitate the movement of the river, lines each of the large ramps. Look closely at the walkway itself to see the fossil-like pattern produced by imprinting blades of bulrush into the wet cement. Even small elements, like the bronze mooring cleats positioned in intervals along the river, were designed by the two artists. The sculptural pieces allow boaters to dock along the entire length of the park.

Anyone familiar with Pittsburgh’s weather might take issue with spending all of this time and energy on a park that, numerous times a year, will be entirely consumed by floodwaters. That unpredictable yet unavoidable fact played a large part in the wildlife used in the park’s design. A considerable amount of time was dedicated to field research — taking boat rides up and down the area’s rivers — in order to identify plant species that thrive in local flood zones.

What ultimately resulted was a planting method Van Valkenburgh deemed “hyper-nature.” The team planted hundreds of red maples, silver maples, native sycamores, river birches, red buds and poplars directly into the riverbank. The over-exaggerated volume of trees created a dense overhead canopy and worked to visually soften the surrounding concrete.

As the designers learned during construction, however, the Allegheny doesn’t only flood during the rainy months. Winter brings car-sized blocks of ice down the river and, when water levels are high, directly into the park. That realization prompted the addition of reinforcements to the walkway and high-pressure water hoses to allow for easy cleanup following a flood.

Needless to say, the scope of the project made the park’s construction a logistical behemoth, with miles of red tape to navigate. The $8 million needed in funding came from both public and private sources, with the state, Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority, and the Vira I. Heinz Endowment all contributing. Money was the least of the team’s problems, since they also had to coordinate with so many different stakeholders during design and construction.

That fact was heavily acknowledged in the report detailing the 2002 EDRA [Environmental Design Research Association]/Places Magazine Place-Making Award the park received. The jurors were “nearly unanimous in their praise for Allegheny Riverfront Park,” with one saying that the space is a “significant place-making in an incredibly difficult urban condition.”

“While the city owned the roadways and the park, the county owned the bridges, the state owned the highway, and the Army Corps had veto power in issues of river navigation and flooding,” wrote David Moffat. “Such a tangle of jurisdictions undoubtedly contributed to this important city edge being lost in the first place. Reclaiming it involved a complex negotiation, including not only design review on aesthetic and social issues, but also complex technical consultations with engineers from a variety of agencies.”

The accolades didn’t stop there. The park also earned a 2002 ASLA [American Society for Landscape Architects] Design Honor Award and a 1997 Progressive Architecture Awards Citation.

The upper tier of the park, lining Fort Duquesne Blvd., opened in 2001. With its unveiling came a seamless transition between city and river, between urban and wild. These days the entirety of Allegheny Riverfront Park sees plenty of regular use. Walkers, joggers, runners, bikers and more all share the path. The park is functional art in perhaps its purest form. As one writer put it, “the most remarkable thing about [Allegheny Riverfront Park] is the way it has completely transformed these two hostile spaces into a welcoming and well-loved public place.”

Maybe you could be its next visitor, engaging with the rivers that built Pittsburgh on their backs.